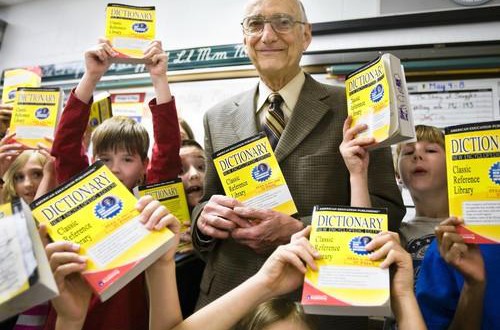

The definition of generosity

Theodore Utchen has given 10,000 dictionaries, plus instructions, to area 3rd graders

He’s been Theodore, Ted and Teddy, depending on the time and circumstances in his life.

But in Wheaton and Glen Ellyn schools, Theodore Utchen is known as ‘Dictionary Man,’ the bespectacled, nattily dressed gentleman who visits 3rd-grade classrooms bearing an unusual gift: a paperback dictionary for every child.

Nowadays, online dictionaries and computer spell checkers abound, and texting and Twittering have ushered in a new world of abbreviated spelling that makes English teachers cringe.

But Utchen, a semi-retired attorney from Wheaton, has managed to captivate the Xbox generation with an old-fashioned learning tool.

‘He has them eating out of the palm of his hand,’ said Denise Urso, a 3rd-grade teacher at Community Consolidated School District 89’s Westfield Elementary School in Glen Ellyn.

Utchen visited her classroom in late March to deliver dictionaries and instruct the 3rd graders on how to use them. On April 20, the District 89 school board commended Utchen for providing dictionaries and instruction to all 3rd graders in four elementary schools.

Over the years, Utchen has given nearly 10,000 dictionaries to 3rd graders in Wheaton and Glen Ellyn school districts.

He started out in 2003 in Wheaton-based Community Unit School District 200, and added Glen Ellyn School District 41 and Community Consolidated School District 89 two years ago.

Throughout this spring, he did 30-minute presentations in 3rd-grade classrooms at 21 elementary schools in those districts. The schedule can be grueling. Utchen jokes that he ‘almost died’ after making five presentations at one District 200 school, followed by three more presentations at another school.

Still, ‘I love it,’ he said. ‘This is the most worthwhile charitable activity I do.’

His philosophy?

‘I feel if we can get kids started early in life with improved communication skills, this will make life more meaningful for them. The secret to great relationships is communication,’ Utchen said.

He said he has always had an interest in English and took a creative writing course in college.

‘Proper spelling and using the right words has always been a hang-up of mine,’ Utchen said.

He chose political science as an undergraduate major, and then decided to pursue the law, graduating from the University of Michigan’s law school. Although he is semi-retired, Utchen still serves as an arbitrator in Cook and DuPage Counties.

After he started working as a lawyer, Utchen found that even grown-ups can find spelling challenging.

He recalls finding misspellings in memos and letters written by attorneys and others. ‘I thought, ‘This is very, very sad,’ ‘ he said.

He also finds scattered misspellings in published materials, such as the newspaper.

He said his interest in providing dictionaries to children developed when he was reading The Wall Street Journal in 2002 and saw a story about Mary French, a woman in South Carolina who had launched a non-profit in the mid-1990s with the intent to distribute free dictionaries to students in her state.

The Dictionary Project continues to this day, and now involves dictionary distributions in all 50 states, French said.

More than 9.9 million dictionaries have been given to schoolchildren, with the help of sponsors such as Utchen.

Most are donated by groups such as Rotary and Kiwanis Clubs, so Utchen stands out as a top individual donor, according to the non-profit’s Web site.

This year, Utchen gave out an American Education Publishing Dictionary, a new encyclopedic edition that also contains information about states, countries and U.S. presidents, and copies of the U.S. Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

When he talks to students, there’s no fancy PowerPoint presentation or Smart Board interactive technology.

He keeps his presentation on nine faded 4-by-6 index cards with his handwriting on the front and back.

He arrives elegantly dressed in a suit and captures students’ attention with an almost musical voice, said Westfield teacher Urso. (Utchen says he was born in St. Paul, Minn., and doesn’t have a distinct accent.)

In her class, Utchen started off by using a sentence containing the word ‘slovenly,’ prompting the children to look up the word to find its meaning, Urso said.

At District 89’s Arbor View Elementary School, ‘He was very charming and very personable. He had kind of an old-fashioned way of telling stories. He was very engaging,’ said 3rd-grade teacher Cathy Yaniz.

She said 3rd grade is a good time to give children dictionaries, because they have developed alphabetizing and sorting skills.

Both Yaniz and Urso say students continue to use their dictionaries after Utchen’s presentation.

While students can use spell check, there are not enough computers in the classroom for every child to access the spelling tool.

‘I see them all day long,’ Yaniz said.

‘There are six kids who have them sitting on top of their desks right now,’ added Urso.

Utchen said he cherishes the thank-you notes he gets from students.

Over the years, several students have offered to help him learn to use a computer.

It may come as a surprise to students that Utchen has a computer, thanks to the urging of his son, a veterinarian in California.

He uses e-mail. He even uses spell check. But he knows that spell check doesn’t catch all spelling errors, so he always keeps a printed version of the dictionary on hand.

A dictionary will stand the test of time, said District 89 Supt. John Perdue.

‘I think there will always be a place for it,’ Perdue said. Even as technology changes the world we live in, ‘our public libraries are not going to cease to exist; textbooks are not going to cease to exist. Neither will a dictionary.’

Dictionary Project note:

We would like to share this letter from one of the teachers whose students received dictionaries from Mr. Utchen.