The Dictionary Lady Spreads the Word

By JUNE KRONHOLZ Staff

Reporter of The WALL STREET JOURNAL

March 4, 2002

To South Carolina Kids Mrs. French Helps 3rd Graders Find Meaning of ‘Success’; Also: ‘Ferocious’ and ‘Respect’

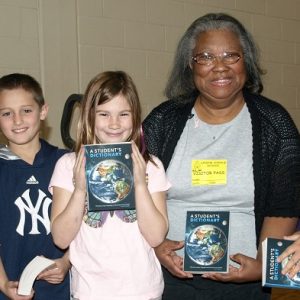

CHARLESTON, S.C.— Six years ago, Mary French set out to give a dictionary to every third grader in every school in South Carolina, every year.

Education “starts with learning how to look things up,” Mrs. French says. It means a certain rigor, uniform expectations, and “doing things properly,” she adds. It means a dictionary, she decided.

There are 44 counties in South Carolina, 86 school districts, 580 elementary schools, 55,000 third graders. The wife of a utility-company supervisor, Mrs. French works alone from the family room of her Charleston tract home and totes dictionaries in the trunk of her 1995 Saturn. She prowls charitable foundations for money, never asking for more than $1,000 and usually getting less. When a Columbia, S.C., school district said it didn’t want her dictionaries, she delivered them anyway and took along a U.S. Congressman to make the point. A small wren of a woman, Mrs. French loses her car in a parking lot, can’t find her way out of the airport and shows up at the wrong hotel for a meeting of school principals, all within an hour. Her conversation flutters from subject to subject, never quite alighting. “People think I’m flaky," she volunteers. “But what makes me eccentric is that I care deeply about nobody being left out.”

This year, for the third year running, no one will be. Mrs. French, who is 44 years old, expects to reach every third grader in South Carolina, and to begin spreading her Dictionary Project to seven other states as well.

Last year, Americans gave $1.5 billion to charities formed to help the Sept. 11 terrorists’ victims. Three people donated to various causes $1 billion or more each. The largest 400 charities raised $43 billion, says the Chronicle of Philanthropy, the biweekly that covers the nonprofit world. The Salvation Army raised $1.4 billion, and $1.4 billion the year before that, too.

And then there are people like Mrs. French, who work on their own philanthropic visions in their own smaller ways. Last year, Mrs. French’s Dictionary Project raised $75,000. That’s almost double its revenue for 2000. The smallest member of the Chronicle’s Philanthropy 400, its list of the year’s biggest fund-raisers, brought in 407 times more than that.

A neighbor does the project’s bookkeeping for free. Mrs. French’s husband, Arno, heads her board. Their children, ages seven and nine, stay late at school to give Mrs. French more time to hand out books and take care of e-mail. She took a $12,000 salary one year, but stopped because, she says, “I hated that it was taking money from the dictionaries.” In a state where 45% of the fourth-graders can barely read, there’s no way to prove that Mrs. French’s dictionaries are helping South Carolina’s third graders. But Gene Huiet, principal of Merriwether Elementary School in North Augusta, near the Georgia border, has received them for six years and says he knows they help. “We’ve got kids who literally read them, who never had a dictionary in the house, and now they’re winners,” he says.

Mrs. French tells a complicated life story that includes dropping out of college in Ohio to take a bike trip across country and abandoning a flower shop in New York because of an abusive business partner. She fled a job as a school-board secretary in New Hampshire–her only paid job in education—because she felt the bleak weather had nudged her toward depression. When she arrived in South Carolina, her five-year plan was to get married, buy a house, have children and finish college, all of which she did. Her 10-year plan was to do something to help the South Carolina schools. That was 10 years ago.

The Dictionary Project began, she says, when she read a letter to the editor in a local newspaper, asking for school dictionaries. Distributing dictionaries, she decided, was a chance to do something for the schools without “looking like you’re meddling.” She scoured bookstores for cheap dictionaries that first year, and delivered 6,500 of them—enough for the third graders in three counties around Charleston. The next year, she doubled that, and the year after that, doubled it again. Along the way, she became known as The Dictionary Lady.

On a rainy morning recently, Mrs. French arrived at Stono Park Elementary in Charleston to hand around her abridged Webster’s Classics to the 92 third graders, then faded into the background. Big words began flying. “Is ‘ferocious’ in here?” asked a boy named Kyle. On the way to page 137 to find out, he stopped at page 110 to announce, “Hey, I found ‘diploma’." His classmate, Chase, proposed that everyone look up “circuitous” (it’s not in there, but “circuit” and “circular” are on page 79). Across the room, Rohan topped that with “photosynthesis,” on page 253.

Mrs. French then hurried off for the two-hour drive to Columbia, where 42 children waited at Carver-Lyon Elementary School. They raced each other to look up “community” and “perhaps” and “immediately.” Then it was Gadsden Elementary, a half-hour into the piney woods, where 24 third graders competed to find "motivate,” “procedure” and “library.”

When the Dictionary Project began, Mrs. French made all the deliveries, but volunteers do many of the school visits now. Politicians love to help and school districts take direct delivery of some of the dictionaries. Still, she visits 50 to 60 schools a year.

A dictionary must include the words "courteous” and “respect” for Mrs. French even to consider giving it away. She believes it should be lightweight enough for small children to want to carry home at night, use type that’s neither too big nor too small, and be neither too hard nor too easy to understand.

For a time, Landoll Inc., an Ohio publisher, supplied Mrs. French with its paperback Webster’s Classic Reference Library Dictionary for 50 cents a copy (“courteous” is on page 95, “respect” on page 274). But in 2000, Tribune Co. sold Landoll to McGraw-Hill Cos. and, nine months later, McGraw-Hill announced a new price—$1.49 for a dictionary that retails for $2.49 on Landoll’s Website. Mrs. French says she badgered Landoll and, when that didn’t work, wrote McGraw Chairman and CEO Harold McGraw III, who assigned two deputies to the issue. She and McGraw-Hill settled on $1.12 a dictionary, shipping included. (A McGraw-Hill spokeswoman calls the first quote “a misunderstanding.”)

Foundation grants and small gifts cover most of the Dictionary Project’s costs. Richard Hendry, vice president of the Community Foundation, which helps people identify charities and manage their giving, calls the Dictionary Project “an easy sell among donors," in part because the schools all know the Dictionary Lady, and in part because Mrs. French asks for so little money. Charmed that Mrs. French asked for only $500, Harriet McDougal, a Charleston resident whose husband writes fantasy fiction under the pen name Robert Jordan, says they decided, “Let’s give her some money and see what she can do with it.”

A meticulous, three-page accounting shows that, at $5,000 each, Ms. McDougal and an order of Catholic nuns were the Dictionary Project’s biggest donors last year. At $10, an Ohio doctor was the smallest. In between are sums from dozens of Rotary Clubs that adopt a few schools each, help hand out the dictionaries, and now have helped spread the project to New Jersey, Ohio and five other states.

Mrs. French knows all of the clubs’ names and locations. On another meticulous three-page accounting, she records how many books each has given away: 2,160 dictionaries from the Cheraw Rotary Club in South Carolina, which has given the most among the clubs; 31 dictionaries from a club in Phillipsburg, Ohio, which has given the fewest.

As Mrs. French sees it, the Gates Foundation, the biggest U.S. philanthropy with $24 billion in assets, operates not much differently from the Dictionary Project, with no assets at all. Microsoft founder Bill Gates “sits at his dining-room table” with his family, she imagines, and “plans his giving. I do too.” Mr. Gates’ vision is huge—finding an AIDS vaccine, improving teacher education, inoculating Third World children against infectious disease.

In its way, Mrs. French’s vision is no less grand. “We are putting words in the hands of children,” she says.