Arlington Elks distribute dictionaries to third graders

For children who are learning to read, a crucial turning point comes during the transition from grade three to grade four.

According to a report published last year by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, a private charitable organization supporting disadvantaged children, students spend their first three years in elementary school mastering reading skills, but when they reach grade four, they pivot from acquiring literacy skills to putting them in practice.

“Reading proficiently by the end of third grade . . . can be a make-or-break benchmark in a child’s educational development,” the report states.

For the past six years, the Arlington Elks Lodge has been helping to highlight the importance of strong vocabulary and literacy skills by distributing dictionaries to every third grader in town. The Lodge is one of approximately 600 that participate in The Dictionary Project, a national effort to place dictionaries in the hands of young students.

The Dictionary Project was founded in 1995 by Mary French, a South Carolina resident who was seeking to improve the quality of education in her state. The primary focus of the project is to promote literacy and support young readers who are beginning to harness the information they read.

The Elks became a sponsor of The Dictionary Project in 2004. Since then, Lodges across the country have donated more than 1.2 million dictionaries to third-grade students and their teachers.

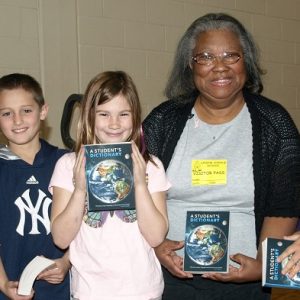

Elks Lodge members Arthur Edgecomb, Jr., Barbara Lynch, Frank Fitzgerald, Rick Daily and Debbie MacDonald visited the Bishop Elementary School on Thursday, Nov. 10 as part of their annual dictionary distribution effort. They handed out copies of the “The Best Dictionary for Students,” a version published by The Dictionary Project, Inc., that is tailored for elementary school students. It includes 32,000 words with “child-friendly” definitions, according to a description online, as well as information on punctuation, the nine parts of speech, weights and measures, Roman numerals, and a map of the United States.

Edgecomb, Jr., a retired math teacher with 37 years of classroom experience, also provided students with a high-energy primer on how to find information in the dictionary.

Speaking after the event, Edgecomb said he fears a shift to digital technology has stripped students of the opportunity to learn about subjects like geography, which are highlighted in the appendices of reference books.

“Everything seems to be computer-generated now,” Edgecomb said, “and I think, as I showed the kids, in the dictionary, there are other things in there besides the words.”

Since The Dictionary Project began nearly two decades ago, opportunities for children to encounter printed books have diminished in many households, according to French. She said receiving a copy of the dictionary is especially meaningful for children who don’t have access to many books at home.

“The children say, ‘This is the only book we have in my house,‘ or, ‘This is my first book that I’ve ever received,’” she said, “and there’s obviously a lot of homes that have a lot of books in them, but I think we’re at a time now, a sort of a crossroads . . . where people don’t have as many books to use as they used to.”

The Dictionary Project is sponsored by approximately 85 private donors and organizations, such as the Elks, and has grown to reach classrooms in all 50 states, according to French.

She stressed that expanding a student’s vocabulary has ramifications beyond reading comprehension.

“Their options for life are pretty limited [without a strong vocabulary] . . .,” she said. “I always tell [students], ‘You earn what you learn.’ The more you learn, the more money you can earn.”

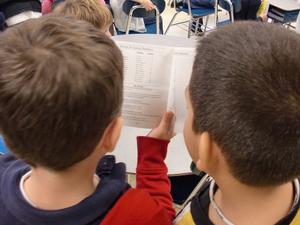

Inside the classroom of Bishop School teacher Maria Amato on Thursday, 8-year-old Filip was among the most enthusiastic dictionary recipients. Leafing through the book, he called over a friend to inspect a list of five “big words.” They paused to contemplate the entry “pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis,” the 45-letter name given to a type of chronic lung disease, which is arguably the longest word in the English language.

“Some of these kids really get into it,” Edgecomb said after the event. “Some kids really make it worth our while to go there."

Read more: Arlington Elks distribute dictionaries to third-graders – – The Arlington Advocate http://www.wickedlocal.com/arlington/mobilenews/x1691082676/Arlington-Elks-distribute-dictionaries-to-third-graders#ixzz1dpmujZhZ